Help Students with Long-Term Illness to Access Learning

When long-term illness stops a student from coming regularly to school, we should be enabling access, not chasing attendance, says Claire Tripp…

- by Claire Tripp

We all have students who shuffle into school knackered. Teens who struggle to get out of bed every morning and we suspect, but don’t say aloud, have been up playing Fortnite till 2am. The ones whose initial enthusiasm, if they had any at all, has waned by Wednesday.

So, when does tiredness become a symptom of something other than late-night computer games or draining social media dramas? At what point do we recognise it as a health problem, instead of judgement on the appropriate bedtime for 14-year-olds?

Emma hasn’t been to school since she was in Year 9, three years ago. The medical evidence says she has Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Her school thinks this means she’s just exhausted and can’t cope with everyday life. In fact she’s seriously ill and coping with more than they could imagine.

An estimated 1% of school-aged children suffer from CFS, more widely known as ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis), and it’s the most common cause of long-term sickness absence from school. It’s life-changing and studies show that 68% of children need an average of five years to recover and get their lives back on track. (Those outside of that statistic need longer or don’t recover.)

Yet, their absence is typically treated by EWOs as an attendance problem. This means the student doesn’t receive the kind of pastoral care we should be giving a child with a serious illness and, more often than is acceptable, can lead to unjustified and traumatic safeguarding proceedings for the family.

The energy drain

It’s hard to appreciate just how debilitating ME is. Most symptoms are invisible: cognitive dysfunction affects a student’s ability to learn, severe muscle pain gets worse after light activity. Students with ME suffer from extreme exhaustion, but this is all too easily misinterpreted as laziness, particularly in teens, who are of course not known for their boundless enthusiasm.

Emma’s life isn’t spontaneous anymore. Her anaerobic system is broken following a virus and doesn’t make enough energy to function at normal levels. Every drop of energy is valuable. Daily activities are limited and carefully balanced so that, instead of just existing, she has some semblance of living. She’s disabled, not tired. And she’s certainly not ‘avoiding school’.

Moreover, it’s easy to underestimate the physical and mental demands of being at school. Students with ME report school is the single most energy-draining activity they can undertake. Yet it’s the activity they find the most distressing to be missing out on and are most determined to resume.

Some students, like Emma, aren’t able to come into school at all. They spend their formative teenage years housebound, socially isolated, and in many cases can’t access even a basic education; a lonely existence at a time when their peers are flipping bottles or still talking about when Miss accidentally set the fire alarm off in science.

The risk of being forgotten by their classmates and teachers is high. Life moves fast in schools. How long does it take for a student to simply be a name on the register, absent for so long we no longer expect to mark them present?

A flexible approach

The good news is that early identification and the right support for a child with ME suggests they have a greater chance of recovery than adults. So the sooner they can reduce their activity and stay within their energy envelope, the better it is for them long-term.

This is where schools play an important role. But it’s hard to see most teens as anything other than lethargic, especially in the classroom. So how are we supposed to know the difference? Particularly when, due to an historic lack of medical education on ME, even doctors can find that difficult!

Fortunately, ME has a unique symptom called post-exertional malaise (PEM) – an abnormal physical response to activity shown as a worsening of or increase in symptoms. In schools, this can be seen even in milder cases, for example, in a drop-off in attendance at the end of the week, or struggling to concentrate fully towards the end of the day.

Continuing to do too much exacerbates the illness and causes PEM, leading to short-term or long-term deterioration. Students managing to come into school need teachers to know the importance of pacing activity and the impact this has on prognosis.

It can be hard for schools to balance the requirement to educate with a student’s health needs. ME fluctuates from day-to-day and is hard to predict. But positive communication with the family will hash out clear priorities and should aim for a highly flexible approach that best meets the student’s long-term goals.

A healthy balance

Whether we think school should be at the top of the list or not, it’s only one piece of the puzzle when looking at the future. So, a healthy balance of education, socialisation and development is needed. Students should remain on roll and feel part of the school – included, even if they aren’t well enough to be there.

A highly-motivated or bright student whose attendance becomes sporadic or who becomes less engaged in lessons will likely give rise to safeguarding concerns, so it’s important schools understand how ME could be a cause for these changes. Families should be spared unnecessary accusations and suspicion.

No-one expects school staff to fully understand ME; it’s a highly complex illness. The key is to seek advice from experts such as Tymes Trust, who take a pragmatic, informed approach in supporting schools, students and families. Guidance will need to be sought on how to meet the requirements of the Equality Act in helping a disabled student access education and the wider school community.

Despite what they say to the contrary, most students would be devastated if forced to miss such a huge chunk of school. Those who do miss out deserve care and compassion; their health needs are paramount. Just as with any other student with a long-term illness.

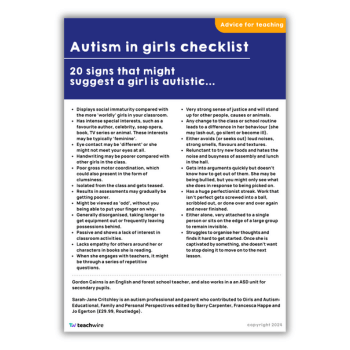

School support – 3 ways to help students with ME

- Cognitive function is affected by ME (a symptom known as brain fog), so involvement from the SENCO is needed. Make sure you apply for exam arrangements, including delayed start times and in some cases sitting the exams at home. jcq.org.uk

- Tymes Trust is an ME charity for young people run by a former head teacher. The website has information specifically for schools and SENCOs, and they can directly help and advise schools with students who have ME. tymestrust.org

- Unrest is an award-winning documentary by Jennifer Brea, who has ME. It gives valuable insight into the daily challenges faced by people with ME and is available to watch on Netflix and Amazon Prime. In the US it forms part of the continuing medical training programme and counts as CPD. Ask your school if they will do the same. unrest.film

Claire Tripp manages her daughter’s education and campaigns for health equality with #MEAction. Follow her on Twitter at @chicaguapa.