Education isn’t just a conveyor belt for the job market

The drive to make schools a force for social mobility risks distorting our collective sense of what education is meant to be for, says Kevin Rooney…

- by Kevin Rooney

What is the core goal of education?

For years now, educationalists and politicians of all hues have been telling us that it is ‘social mobility’ – that is, reducing poverty and inequality, while promoting mobility up the social ladder, especially for poor working class and black pupils.

Schools minister Nick Gibb informs us that, “A welcome consensus has begun to emerge that schools must be engines of social mobility.”

London schools, in particular, are held up as a great success story.

I wish I could share that rosy narrative.

For me, the social mobility agenda is distorting and degrading education in a number of ways.

Many schools have become boring, technocratic institutions where formulaic lessons, teaching to the test and high stakes accountability measures are now the norm. I fear this approach is sucking the life and joy out of teaching and learning.

In practice, social mobility means preparing pupils for the workplace and a successful career.

There doesn’t seem to be much debate between left and right on this issue – the left might prefer to call it ‘social justice’ rather than social mobility, but they’re just as eager as the right to talk about the role of schools in securing jobs for their students.

Increasingly, schools are being judged not just on their exam results, or even the number and type of universities their pupils go on to attend, but also the type of jobs their ex-pupils take up.

That’s precisely why teachers resort to exhortations about the need to ‘work harder’ in lessons, in order to get that Level 8 or 9 GCSE grade.

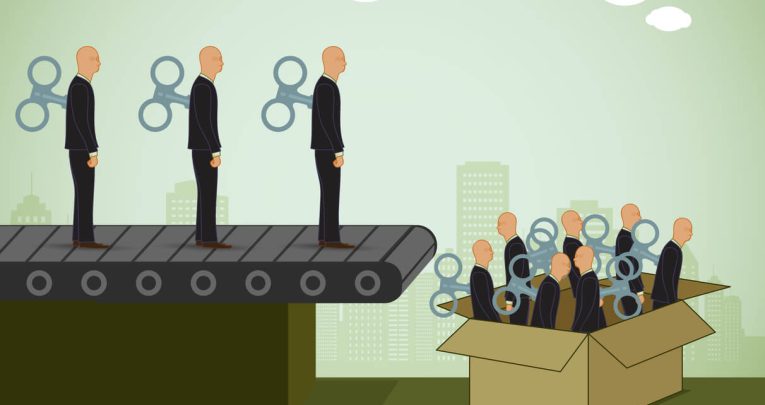

The rise of scripted lessons, knowledge organisers and even the use of cognitive load theory have all contributed to this factory model, where schools are essentially putting pupils onto conveyor belts who can fill job vacancies and meet the wider needs of employers and UK PLC.

‘Can you stop now?’

Our students have become socialised into thinking that the only thing of value worth learning is that which will appear in the exam paper.

I had a taste of this myself during a pre-lockdown Y10 history lesson, when answering a question about the Battle of the Somme.

I went off on a tangent – contemplating whether WWI was an imperialist war in which Britain was equally culpable, or whether Britain was a progressive force in a war to defend democracy – and was in full flow, when one of the most conscientious and brightest girls in the lesson interrupted to say, “Sir, if the stuff you’re talking about isn’t in the exam, can you stop now and get back to the stuff we need to know for the exam?”

Deflated, but knowing full well that school leaders and parents would probably take her side, I went back to teaching my pre-prepared lesson plan.

Later that day I asked my other exam classes, “Who thinks teachers should stick to talking about and teaching what’s likely to come up in the exam?” An overwhelming majority in each class raised their hands in support of sticking to teaching to the test.

When I then asked these classes what they thought education was for, they looked bemused. “To get a well paid job, of course,” came the answer. Is it therefore any wonder that many students found themselves disoriented by the cancellation of their exams during this year’s pandemic, or that they questioned whether there was any point in continuing to study?

It’s come to something when even the exam watchdog, Ofqual, is worried that things are getting out of hand. A report published by Qfqual in February stated that when teaching GCSE and A Level pupils, teachers must stop using scare tactics, such as warnings about future job prospects.

Ofqual sadly doesn’t challenge the fundamental idea that exam success should be linked to better job prospects, but rather worries that these sorts of dire warnings will be counterproductive:

“High levels of test anxiety are generally associated with small reductions in test performance. As such, test anxiety could have a detrimental impact on performance in high stakes assessments, with further implications for entry to subsequent education and employment.”

The exam regulator also notes that teachers under pressure from high stakes accountability measures may result in a ‘transference of stress’ onto students.

The pursuit of wisdom

We should remember that the act of preparing children for the jobs market is different to educating children in a number of important ways. The former is glorified job training.

The latter is about the transmission of a body of knowledge and the tools to allow learning, linked to the cultivation of intellectual curiosity.

This involves helping pupils acquire the habits of introspection, discernment, self-awareness and empathy. Across the arts, sciences and humanities, our young people should be engaged in the pursuit of wisdom.

In my model of a school, the pursuit of knowledge and ideas has an intrinsic value.

As Ofqual itself notes, when a student is unmotivated, the teacher will often increasingly resort to warning them about their future job prospects.

Instead, teachers should start from the premise that the particular subject under discussion is worth knowing, and recognise that our responsibility as good teachers is to intellectually convince the pupil why a subject is worth getting to grips with.

The social mobility mindset is so deeply embedded that to challenge it is to risk being perceived as callous. But if you want to bring about social mobility, it would be better to get involved in politics and fight for policies that might reduce poverty and inequality.

Viewing schools as an engine for social mobility degrades education and distorts the role of the teachers.

If we lose sight of the intrinsic value of education and allow a utilitarian model of education to take over, the teacher-pupil relationship will become merely a transactional one, as education itself becomes imbued with a set of instrumentalist goals.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to get a fulfilling and well-paid job. I’m a great fan of careers advisers and of schools collaborating with local employers, but these things have historically been a by-product of what a good school does, and have taken place outside of the classroom.

My wife is prone to telling people that I’m a useless husband and father but a great teacher. She’s kept every one of the cards I’ve received over many years from students leaving 6th form.

Most of those students received excellent exam results and were heading off to good universities, but what they were thanking me for was something different. It was for inspiring them with a love of learning and a love of subject, and for triggering in them a wider intellectual curiosity.

The slow change we’ve seen in the purpose of schools is sad for teachers, students and parents alike. We need to reclaim it.

Kevin Rooney is a teacher, author, and convenor of the Academy of Ideas Education Forum.