Helicopter Stories – Let kids’ imaginations fly

Ready to take your classroom on a storytelling adventure that sparks creativity, collaboration and endless smiles? Buckle up and explore the incredible world of Helicopter Stories…

- by Trisha Lee

Overview

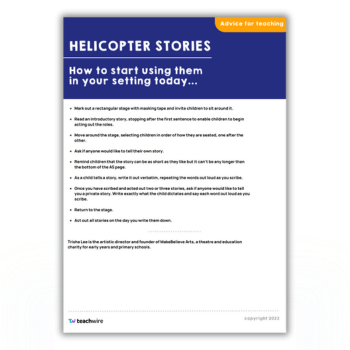

In theory, Helicopter Stories is a simple approach. The teacher or workshop leader scribes children’s stories, word-for-word, then the class comes together to act them out.

You need minimal equipment: a roll of masking tape, several sheets of A5 paper, a pen and a practitioner who is curious to uncover the dexterity of children’s imaginations.

“This is an inclusive, whole-class approach where every contribution is valued”

In action, it is a highly effective learning strategy. Children get the chance to share something that is of huge importance to them: their story.

They develop their speaking and listening skills as they pay attention, and respond to each story from their class. When we scribe children’s words verbatim, they make the connection between the spoken and the written word.

This is an inclusive, whole-class approach where every contribution is valued. Scribing a story for a child, and supporting them to act it out, is a great privilege. It’s an invitation to us adults to step back into an enchanted place, the one that only children inhabit.

How does it work?

Based on the work of Vivian Gussin Paley in Storytelling and Story Acting, Helicopter Stories is a highly reflective approach that engages children in one of the things they know best: making up stories. Here’s how it works…

- A child tells their story

- You, as the adult, scribe it word for word

- The child decides which character they would like to play

- The class gathers to act the story out

This is child-centred learning. The story belongs to the individual and because we don’t lead, but instead allowing children the freedom to create in the way they want to, beautiful tales are born and rich learning takes place.

“Beautiful tales are born and rich learning takes place”

In Helicopter Stories, we respect children’s words. By taking it in turns to act these words out, children learn to play cooperatively with each other.

Throughout the process they are able to demonstrate how they take account of one another’s ideas, allowing each other to interpret the stories of the class and work together to breathe new life into them.

They comfortably adapt their responses, taking on the roles of listeners, storytellers and actors. You’ll see them shifting seamlessly between these, as each new story emerges.

Every child has the chance to shine with Helicopter Stories. Even quiet and shy children clamour to share their ideas and deepest thoughts. A Helicopter Stories environment is one where we:

- recognise children’s gifts

- bring a whole group together

- nurture the creativity of all pupils

Helicopter Stories can unlock children’s voices and set their imagination free, helping them to grow.

Benefits of Helicopter Stories

Helicopter Stories allow us to tap into the world of the child in a way that nothing else does. Through using the approach on a regular basis, we can see, and value, the expertise in the children we work with and discover the unique way they see the world.

Helicopter Stories is the only approach I know where even the quietest child clamours to open their mouth, to share their story and imagination, to stand bravely in front of their peers and portray their deepest thoughts, characters and interactions.

“The personal, social and emotional benefits of Helicopter Stories continue to astound me”

It’s a place where children who are overlooked suddenly find themselves in an environment where their gifts are recognised and where they can shine.

The personal, social and emotional benefits of Helicopter Stories continue to astound me with every new anecdote I hear. The process is simple, and you can easily incorporate it into any setting on a daily or weekly basis.

Ingenious mark-making

In today’s digital age, how often do our children see adults write? Perhaps for a shopping list, or a scribbled note, or to record an observation.

In Helicopter Stories, we write the thing that is most precious to the child, their story, as they watch. They witness first-hand how writing captures their words, and perceive how ingenious mark-making is.

Often they become self-motivated and find their own way to explore the connection between the spoken and the written word that is such a vital part of early literacy.

Teachers have remarked how “children’s stories have got longer and more descriptive. They are adapting ideas from their peers. The work makes the children feel like part of a group. They learn how to take turns… everyone is accepted and no one is judged.”

Recently, in a school labelled ‘requires improvement’, I was told that the teacher had been monitoring her children’s progress towards the Early Learning Goals for six weeks prior to incorporating Helicopter Stories. Their progress was good. She carried on monitoring the children for the following six weeks as she introduced the approach, during which time the children continued to make progress at an accelerated pace.

None of this should come as a shock. Helicopter Stories sets children free and allows us to witness their imaginations fly.

Examples and success stories

A teacher who had been using Helicopter Stories on a weekly basis for over a year told me that the one thing she likes best about the work is the opportunity it gives her to find out what really matters to her children.

Now she gets to see a side of each child that she normally never witnesses: the part where they are confident, where they have a safe space to take risks and where they demonstrate their learning at their own pace, around their own agenda.

Making connections

The following story was told to my colleague, Isla, on a Helicopter Stories day in a setting in Havering.

“Once upon a time there was a little girl who was gone all over the place, gone to China. A monster came to China and he was stamping around all over the world.

“And the big monster did jump all the way to Antarctica and he was freezing cold. And he jumped into Indonesia, and he jumped all the way to Canada.” – Alex, aged three

Alex was delighted to be dictating his story and looked in different directions as he spoke, as if tracking the monster’s journey in his mind.

The adults in the room were surprised. Somehow Alex had acquired the names of countries he had never visited, and information on each, such as the fact that Antarctica is freezing.

“Somehow Alex had acquired the names of countries he had never visited”

Even his mother wasn’t sure where the information came from. However, perhaps through something he’d watched or something he’d heard, Alex made the connections and demonstrated that in his story.

Through scribing and leading the class in acting Alex’s story out, the practitioners in Havering learnt something new about this three-year-old: they discovered his expertise.

And there is great potential for this to be developed. How wonderful it would be to show him pictures of other countries, or objects from around the world, to enable him to explore the tastes and flavours of these different places.

Specialist subjects

Meanwhile, in another nursery, I was told a story by a three-year-old Polish boy, who spoke very little English. His story was simple, “Dinosaur, raaah.”

Trending

When we came to act the story out, I asked him to show me how the dinosaur moved. I expected him to run around the stage roaring loudly. The boy surprised me.

“When I said the word he nodded at me, with a big smile on his face”

He formed each hand into three talons, held his arms close to his body so they seemed shorter than normal, and turning his neck from side to side, looked around him out of menacing eyes.

I knew immediately that he was a Tyrannosaurus, and when I said the word he nodded at me, with a big smile on his face.

Again, we learnt so much about the child, his passions, what interested him and his own type of expertise. This child might not have been able to communicate the depth of his knowledge through language, but one look at the detail contained in his acting out, and I could see the intricate knowledge he had about his specialist subject.

“Quiet girl”

“Once upon a time there lived a girl called Ella. She was very pretty, until one day she got her dress all mucky. And her mum and dad were very cross. They locked her in her bedroom for one year. And she was never naughty again.”

Martha, aged five, told me this story. She was “a quiet girl, who rarely spoke” according to her teacher, and yet to me she was confident and articulate.

Later, when she stood on the stage to act out her story, this five-year-old, who normally shied away from the limelight, twirled in her imaginary dress, before raising her hands in disgust to demonstrate how she was now ‘all mucky’.

Two children from around the stage came up to take on the role of her parents. Another group of six children created the walls of her bedroom. They stood around her, forming a prison.

The girl in the story looked out through the walls of children, peering at the class with the saddest of eyes. Martha was in her element. When we applauded, she smiled coyly, the pride in what she had just achieved flushed across her cheeks.

“That was a big punishment for that girl, just for getting her dress dirty,” I said. “Mmmm,” she nodded, and skipped back to her place in the circle, her face alight with smiles.

Making friends

Another teacher shared with me the story of a boy who was struggling to make friends. Days after she incorporated Helicopter Stories into her setting, his situation changed.

The teacher observed the class sitting up and taking notice when they realised how good he was at pretending to be a monster. The invitations for tea soon followed…

Speech, language and learning difficulties

Once, while observing Helicopter Stories practitioner Vivian Gussin Paley at work, I witnessed a conversation between her and a class teacher who suggested that it might be best to remove a young boy with autism, who could be “difficult”, from the class in order to minimise disruption.

Vivian declined, saying that if he was usually part of the class, he should stay.

The boy proceeded to roll around the stage playing with plastic animals, while others in the class continued with their acting. When he brought these animals to Vivian’s feet, her attention moved entirely to him, watching the way he played, un-invasively dictating and transcribing his story.

I’ve received similar questions in sessions myself, and they’re always asked with the best of intentions. Interruptions however, are the lifeblood of any classroom – and how we deal with them sets out the morality of our work.

“Interruptions are the lifeblood of any classroom”

In one Reception class, after weeks of watching Helicopter Stories, we observed a selectively mute girl simply whisper the word ‘princess’.

That’s the secret to the approach – there’s no pressure placed on the children. It’s an activity in which they cannot fail. All pupils can contribute a story, but if they’d rather not, they can still be involved through acting for their classmates’ stories, or by listening to the tales of others.

Every child is different and brings value to the world in their own way. By respecting their perspective, we show that we understand them and value them. This inspires their self-confidence and helps to foster their willingness to participate in activities.

Breaking language barriers

For children with language difficulties, Helicopter Stories can tell you just as much about a child as their verbal communication skills.

Young children don’t learn to speak through repetition of words, but through immersing themselves completely in the language. Story acting allows pupils to create a story with a clear theme, narrative and resolution, without necessarily having to use any words.

I’ve previously observed one boy in Tower Hamlets vocalise an entire story about a car that drove too fast and crashed, using sounds like ‘Brrrrrrrm‘ and ‘Eeeeeeeeeeeek‘. I attempted to scribe these sounds exactly and repeated them alongside his on-stage movements. The pupils watching were captivated, gasping at the dramatic conclusion and applauding him.

Safe spaces

The Helicopter Stories approach can help to develop a sense of community in your classroom, so that the experiences and needs of all the children are understood and valued.

High-achieving pupils can exercise their creativity, while children with language or learning difficulties can work alongside them in an inclusive environment. Pupils’ words are respected by the group, and no child is made to feel judged.

It also helps to create a safe space in which children can address issues in their own lives. At Chisenhale Primary (one of four certified MakeBelieve Arts Helicopter Stories Centres of Excellence), one of the pupils had recently left for Australia.

“No child is made to feel judged”

The issue hadn’t really been discussed until one girl took to the stage with the words, “This story is a little bit sad”. She went on to tell the tale of a girl named Daisy who had moved away. She put herself into the story, explaining her feelings. It was her way of saying ‘I miss my friend. I hope she comes back.‘

On stage, children can express negative emotions such as sadness or anger in a way that helps them to process upsetting events and experiences. They may playfully present something distressing. This can inform you about what is troubling a pupil. You can then find resolutions by working through the scene.

Research

The Helicopter Stories approach has been evaluated by the Open University, who found it to have a significant impact on communication, literacy, speaking and listening.

Resources and training

To find out more about Helicopter Stories, read Trisha Lee’s book, Princesses, Dragons and Helicopter Stories.

Helicopter Stories On Demand gives up to four members of your team, one year’s access to an online training course. It includes everything you need to begin delivering Helicopter Stories in your setting.

Trisha Lee is the artistic director and founder of MakeBelieve Arts, a theatre and education charity for early years and primary schools. Follow Trisha on Twitter at @TrishaLeeWrites.