Collective punishment – Is it always wrong in schools?

What is collective punishment and does it work? What are the alternatives? We explore this controversial teaching tactic…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

What is collective punishment?

Collective punishment refers to the practice of disciplining a group of students for the actions of one or a few individuals within that group.

This method assumes that holding the entire group accountable will encourage students to regulate each other’s behaviour and prevent misconduct.

Is collective punishment legal in school?

In UK schools, collective punishment is legal. There is no specific legislation that prohibits collective punishment.

However, the Department for Education’s guidelines emphasise that any disciplinary measures should be consistent, fair and proportionate. The guidelines encourage schools to focus on individual accountability and ensure that they justly apply punishments.

Ultimately, the decision to use collective punishment lies with individual schools and educators.

Does collective punishment work?

Does this tempting ‘last resort’ technique have a counterproductive impact? Penny Rabiger investigates…

Collective punishment is as much punishment for those who behave themselves, as it is for those who don’t. It seems perverse to me that we punish those who have done nothing to deserve it.

We teach them that there is no reason to behave well. If we don’t recognise (or even disrespect) their efforts to follow the rules, these students eventually may say, ‘Pfff! What’s the point?’

“It seems perverse to me that we punish those who have done nothing to deserve it”

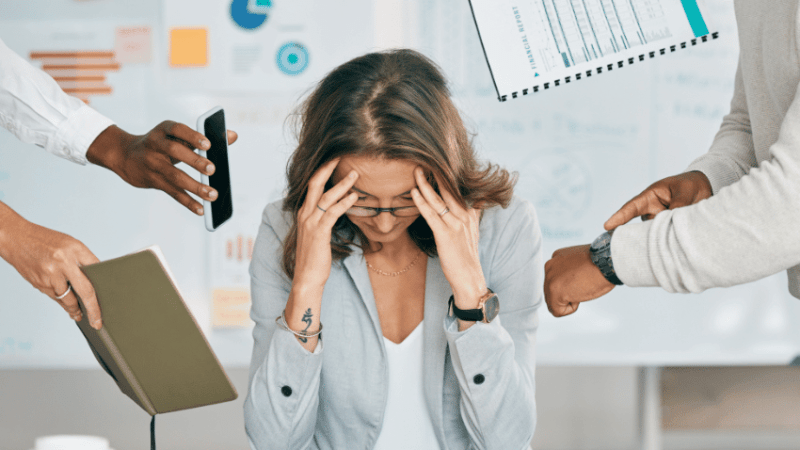

In the past I have given collective punishment. It was many years ago. However, I can still see the ghost of sheer desperation and the feeling of vindictive hatred towards those who had wrecked my well-intended, well-planned lesson.

Sooner or later, I must have realised it was wrong. Or perhaps I just got better at managing behaviour in class and seeing who was misbehaving and needed sorting out.

If you are ever tempted to deploy collective punishment, here is a short film about how ridiculous it is.

Reasons to avoid collective punishment

- It makes you look weak and too lazy to get to the bottom of who is misbehaving

- Your school behaviour policy probably doesn’t allow it. This means that you are not only breaking the rules yourself but you’re also breaking the contract that each child and teacher has signed up to in the school

- It demotivates well-behaved students and can discourage them from behaving well altogether

- It makes you feel horrible about yourself as a teacher

- It doesn’t make sense. We don’t close entire roads because some people drink and drive. Neither do we shut down libraries because some people damage the books

- There are better ways

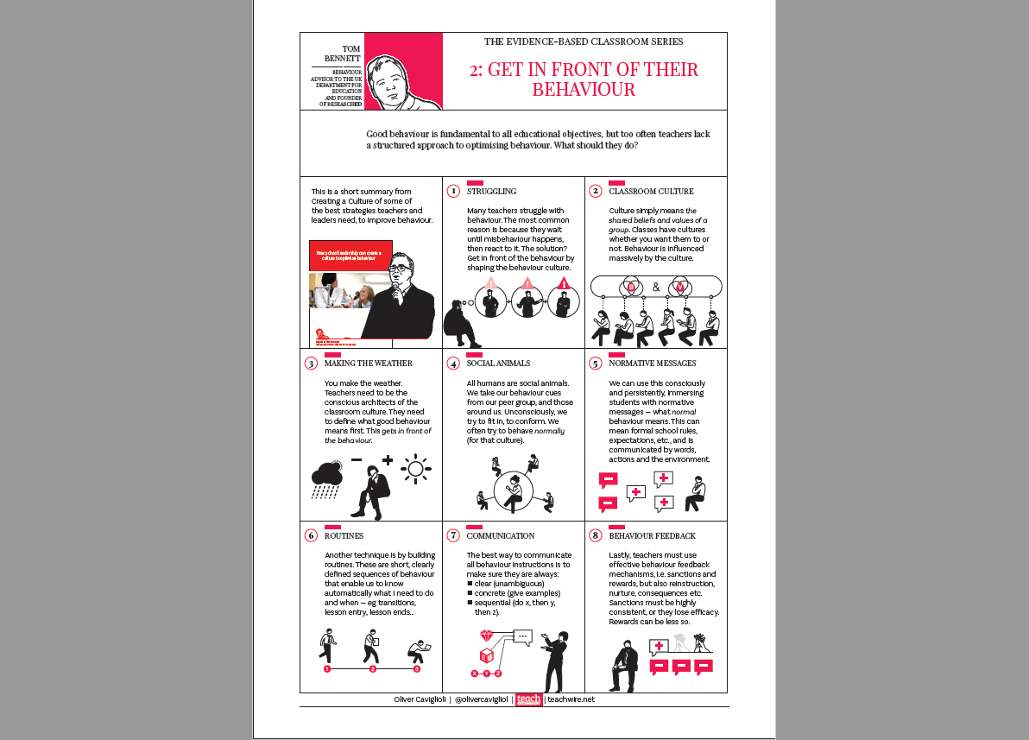

Alternatives to collective punishment

If you need other ways to punish those that misbehave, here are some people with a few ideas:

- Learning Spy deploys an approach which involves gradually releasing students until you can identify the right person and deal with them.

- Larry Ferlazzo, in The Happy School, advocates a gentle approach that happens more discreetly than the public display of anger and disappointment in front of the whole class that often takes place.

- Playworks suggests six ways teachers can build a collaborative contract with their students so collective punishment, such as withholding break time, doesn’t have to be an option.

Case study – Keeping all kids engaged

There is a Spanish teacher at my kids’ school who commands respect from all students. We often hear about them over the dinner table.

This teacher seems to know a key fact about each student and uses it to draw out of them a level of engagement and concentration that is stunning.

One boy can’t sit still and often loses concentration. He is a great artist. The teacher asks him to summarise the key points of the lesson in a series of drawings. The teacher shares these with other students at the end of the lesson to complement their own notes.

He is riveted and gets stuck in. His own understanding has increased and he is proving to be a great student where, in other classes, he is disruptive and disengaged.

Trending

Special role

One student always shouts out inane things that cross his mind. Sometimes he shouts answers to questions without permission, and over the top of other students who the teacher has invited to speak.

The teacher gives him his role at the start of the lesson. The student gets a vocabulary list of phrases and words in Spanish like “how interesting” and “ridiculous”.

He must make remarks appropriately using these words when classmates are speaking. It’s fun and keeps others on their toes.

They want to get things right because it’s hilarious making him interact with them. He is bristling with concentration, not wanting to miss an opportunity to shout out.

Finally, when the teacher is telling them a story or explaining something and uses the word that means ‘but’, the class must catch him and call out “pero means but”!

It’s hardly surprising that most of the class wants to do GCSE Spanish, and he doesn’t ever encounter behaviour problems.

This might seem like an energy-intensive method to engage a class but it seems to work, and I bet he will never give collective punishment in his life.

Letter from a Year 9 student about collective punishment

It is necessary to listen to and follow the teacher’s instructions so that the teacher can get on with teaching us. On the other hand, I am a perfectly obedient student, I always do as I am told and rarely talk in class.

And yet, I still get punished for other people’s bad behaviour every day.

Therefore, I feel that there is no point in behaving well because I am going to be punished no matter what I do.

This attitude or mindset I have developed has been brought on by teachers like you, who insist on punishing the whole group/class for one or two people’s bad behaviour.

This type of behaviour is unfair and unjust and I don’t think I can withstand it any longer.

If somebody is misbehaving, punish them individually (this is fair). I don’t mind being punished if I know I deserve the punishment, but, being punished through no fault of my own is just unfair.

Although it is important for the students to follow the rules, it is also important to treat us as students fairly and respectfully.

Penny Rabiger was an English teacher for 10 years, has since been a director at The Key service for school leaders and governors, head of membership at Challenge Partners, and now works freelance supporting a range of education organisations. She is a keen blogger, Chair of Governors at a primary school, member of the Board of Trustees at a multi-academy trust and a steering group member of the BAMEed Network.