Learning To Read Is A Complex Process, So We Need To Make Sure That It Isn’t Reduced To One Strategy

To develop our children’s early comprehension skills, we must find ways to harness their inner drive to engage with print

- by Anjali Patel

We live in a print-dependent culture so children see us engaging with words in a variety of ways and naturally they are keen to join in.

We write ourselves reminders and notes, fill in forms, and read letters, signs, newspapers, magazines and books – as well as sending and receiving emails and SMS messages, and using social media. Whilst we are doing this we are modelling literate behaviour to our young observers, who will mimic this interaction with print and the meaning it promises.

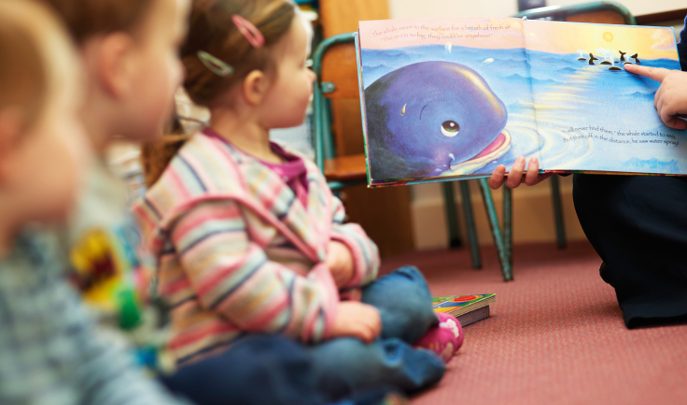

Children who have had a good balance of sharing high-quality texts with enthusiastic adults whilst simultaneously being encouraged to take an interest in, and tune in to, the print itself are more likely to want to read. We know reading takes practice and needs stamina, and this relies on maintaining the interest of our earliest readers. We need to harness children’s drive to find meaning in print; to support them in lifting words off the page, rather than merely barking at text that holds little significance for them.

Teaching strategies

Young children ascribe meaning through their mark making and, when reciting and eventually reading familiar stories from memory, draw on the prosody of the narrative to suggest meaning. Learning to read is a complex human process and we need to make sure that teaching reading isn’t reduced to just one strategy.

Dependence on synthetic phonics may win immediate gains but these are shown to be short-lived, making little academic difference later on if not aligned with reading for meaning.

Understanding children’s stages of development when learning to read combined with knowing about the pedagogy that supports the orchestration of strategies and cues helps us to develop well-rounded readers who read for meaning and pleasure. Every child brings a unique perspective to a text based on their own life, language and reading experiences.

All children deserve to be actively involved in making personal sense of texts and interpreting the world through their relationship with book characters.

Engaging in dialogue around books is an obvious way to develop understanding and so the books you share need to be inspiring. Tune in to a child’s fascinations and draw on your knowledge of high-quality texts that will stimulate interest and discussion. Choose books to share and read aloud to which children can make connections to their own experiences or stories they already know. Share stories that help children deal with important themes and interpret their world. Seek out illustrations that add extra layers of meaning to the text and promote discussion or even role play. Revel in language that is used in lively, inventive ways.

There are a few key teaching approaches that CLPE’s research shows work well in developing deeper response to texts supporting the development of inferential understanding from a very young age, and they are outlined below.

Booktalk

Aidan Chambers’ (aidanchambers.co.uk) work on developing ‘book talk’ began with his interest in why adults formed book groups. Why do we need to relate to others about the books we have read, the stories we have been touched by? His observations suggest that rather than being a solitary experience, there is a social nature to reading; that we seek to share our personal responses and find confirmation in them. Through discussion and debate, we may take more meaning from the reading experience.

Getting talk started Once they have heard a book read aloud, your class can begin to explore their responses to it with the help of what Chambers calls “the four basic questions”. These questions give children accessible starting points for discussion:

• Tell me, was there anything you liked about this book?

• Was there anything that you particularly disliked?

• Was there anything that puzzled you? Do you have any questions?

• Does it remind you of anything you know, in stories or real life?

The openness of these questions encourages every child to feel that they have something to say. They allow everyone to take part in arriving at a shared view without the fear of the ‘wrong’ answer. It is enabling and inclusive, and works beautifully with even very young children. It embraces the knowledge that each child brings something unique to the reading experience and the sustained shared thinking that follows.

As children reply, it can be useful to write down what they say under the headings ‘Likes’, ‘Dislikes’, ‘Puzzles’ and ‘Patterns’. This written record helps to map out the class’s view of the important meaning and is a way of holding on to ideas for later. Asking these questions leads children inevitably into a fuller discussion. They can respond to a particular illustration as well as to the text. As the children grow, they will have internalised the prompts and will use them as a scaffold for discussion of any kind.

Re-enactment and role play

Revisiting stories through a range of play-based experiences helps children to step into the world of the book and to explore it more actively. Through role play and drama, children are encouraged to experiment with the ‘what if?’ of plot and make it their own. Role play is a particularly effective way for children to inhabit a fictional world, imagining what the world of the story would be like, and illuminating it with their own experience. It enables children to put themselves into particular characters’ shoes and imagine how things would look from that point of view. Through drama and role play children can imagine characters’ body language, behaviour and tones of voice in ways that they can draw on later when they write.

Role play in action…

Freeze-frame Freeze-frames are still images or tableaux. They can be used to enable groups of children to examine a key event or situation from a story and decide in detail how it could be represented. When presenting the freeze-frame, one of the group could act as a commentator to talk through what is happening in their version of the scene, or individual characters can be asked to speak their thoughts out loud.

Thought-tracking This technique is often used in conjunction with freeze-frame. Individuals are invited to voice their thoughts or feelings aloud using just a few words. This can be done by tapping each person on the shoulder or holding a cardboard ‘thought-bubble’ above their head. Alternatively, thought-tracking can involve other members of the class speaking a chosen character’s thoughts aloud for them.

Hot-seating When hot-seating with young, inexperienced children, an adult role plays a central character from a poem or story and is interviewed by the children. This activity involves children closely examining a character’s motivation and responses. Before the hot-seating, they need to discuss what it is they want to know and identify questions they want answering. When the children become more experienced in hot-seating, they delight in taking on the role of the central character.

Responding to illustration

In the best picture books, illustration and text work closely together to create meanings. Children are naturally drawn to the illustrations in a book and are frequently far more observant than an adult reader. Children’s interest in images and their ability to read them can be developed through carefully planned interventions with an emphasis on talk. Discussions of this kind can include all children and help to make print more accessible.

The children’s books featured on CLPE’s Power of Reading project, for example, have been chosen because of the quality of the illustrations they contain and the ways in which the illustrations work with the text to create meaning for the reader.

Children will need time and opportunities to enjoy and respond to the pictures, and to talk together about what the illustrations contribute to their understanding of the text. Children can develop their responses to the book by creating artwork in a style similar to the illustrations, and you’ll find other suggestions as to how to take advantage of illustrations in the panel on this page.

USING PICTURES

It’s simple to harness illustrations to engage children in the stories they encounter. Try these five approaches

1. Introducing a new book with a key illustration intrigues and motivates children to want to find out more. You can elicit the children’s initial responses to a character, make predictions and draw connections. The best illustration for this is often not the cover illustration, so always read and engage with the text first to ensure your chosen illustration will provoke response.

2. Conceal part of an illustration from a text to provoke discussion, then provide the complete image to demonstrate how your interpretation changes according to the amount of information you are given.

3. Ask children to list what they can tell about a character from an illustration, his/her appearance, life and personality. Prepare a ‘role on the wall’ or enlarged outline of the character to which children’s responses can be scribed – appearance and facts on the outside, and personality or emotions on the inside.

4. Ask children to think what characters in an illustration might be thinking. This, alongside role play and freeze-frame, could lead to writing in role.

5. Ask children to raise their own questions about the puzzles in a given image, using the Aidan Chambers ‘Tell me’ approach.

Anjali Patel is an early years and primary advisory teacher at the CLPE.

The Centre for Primary Literacy’s Power of Reading training programme supports schools in raising engagement and attainment in reading and writing for all pupils. The Power of Reading website (accessible by subscription here) provides access to an extensive bank of teaching sequences and materials developed to complement the training. Register at clpe.org.uk to receive information about further training and free resources.