National Apprenticeship Week – Resources and ideas for 2025

As National Apprenticeship Week gets under way, we look at what companies are doing to mark the occasion and the difference that apprenticing has made to some young people’s lives…

- by Teachwire

- Classroom expertise and free resources for teachers

Traditionally, schools have often encouraged young people to pursue university. However, with rising fees and no guaranteed job at the end of a degree, many students are now exploring apprenticeships as a valuable alternative. National Apprenticeship Week is a great time to highlight these opportunities, showcasing the benefits of earning while learning and gaining hands-on experience in a range of industries.

Your students may be interested to learn that there are 70 local authorities in England, 19 local authorities in Scotland and five principal areas in Wales where apprentices could get a mortgage as a solo buyer in their 20s, like Molly Caffrey, 21, a degree apprentice at BAE Systems in Glasgow.

What is National Apprenticeship Week?

National Apprenticeship Week is an annual event that celebrates apprenticeships and their impact on individuals, employers and the economy.

It highlights the benefits of apprenticeships as a pathway to careers, with events, resources and employer engagement opportunities designed to help students explore vocational routes.

It’s a great opportunity to introduce students to alternative post-16 and post-18 options beyond university.

When is National Apprenticeship Week 2025?

National Apprenticeship Week takes place between 10th-14th February 2025.

National Apprenticeship Week resources

Toolkit for schools

Download a Schools, Colleges and Providers Toolkit to help you shout about National Apprenticeship Week at your school.

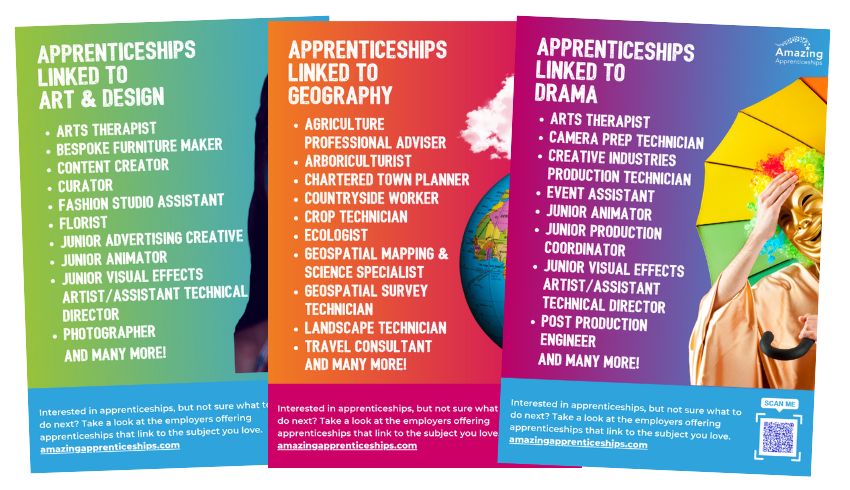

Amazing Apprenticeships resources

You can also download subject-led resource bundles, display materials, classroom activities and more from the Amazing Apprenticeships website.

The Big Assembly

The Big Assembly is a live broadcast on 11th February 2025 at 11am all about apprenticeships. The event will include apprenticeship myth-busting, Q&As, feedback from employers, as well as former and current apprentices.

Online events

The Festival of Apprenticeships is a free online event is a one-stop shop for anyone looking to learn more about apprenticeships. The event will cover everything from discovering opportunities with organisations first-hand to guidance on how to apply for and make the most of an apprenticeship.

Students can join Unifrog’s virtual fair on 12th February to learn all about the world of apprenticeships. Explore the latest apprenticeship opportunities, attend live sessions with top employers and network one-on-one with professional experts.

BBC Bitesize Careers

BBC Bitesize Careers has everything you and your students need to mark National Apprenticeship Week. There are free videos, quizzes and activities for your classroom, with short and flexible pre-planned guides that can be used in tutor time, subject lessons or as homework.

British Army apprenticeships

British Army Supporting Education has created a free assembly resource that helps you challenge misconceptions, showcase apprenticeships and explore opportunities within the British Army.

How to find apprenticeships

- Encourage the young people you work with to explore the wide range of apprenticeships available on the Find an apprenticeship website.

- GetMyFirstJob is a web platform that works with employers and training providers to match young people to the right apprenticeship. For more information, visit GetMyFirstJob.co.uk.

- RateMyApprenticeship.co.uk is like TripAdvisor, but for jobs and careers advice. It’s home to thousands of reviews left by apprentices across the UK.

- Search for an apprenticeship using UCAS’ apprenticeship search.

- Career Map’s algorithms work to match students with employers who are the perfect fit for their skills, aspirations and goals.

Apprenticeship case studies

Apprenticeship schemes aren’t just for people who fail to get the grades; they’re for people who want a more work-based learning approach.

View more apprentice ambassador stories on the Apprenticeships website.

Journalism

According to Bekah Leonard, 19, a journalism apprentice, ‘Late in my A-levels I realised I couldn’t spend another three years of my life learning from a book – I wanted to be getting published and earning some money.

I searched for journalism jobs in London through Twitter and found a journalism apprenticeship. I hadn’t even heard of journalism apprenticeships until then, and have now almost finished the course with an NCTJ Level three diploma and a job doing what I love, while I learn.’

Sales

Apex Stainless Fasteners in Rugby is a major supplier of stainless steel fasteners, making bolts for motorway bridges and screws for the automotive industry.

Michael Westley, 17, started his sales apprenticeship after leaving school. As well as receiving on-the-job training, Michael is working towards an NVQ in Business Administration.

‘There is a lot to learn and every day is different,’ he says. ‘I really like being part of the team, and I am much happier learning in the workplace rather than being stuck in a classroom. It’s great to get the experience while earning your own money.’

Digital marketing

Amelia Sayce took up a digital marketing apprenticeship at The Den Kit Company after her A Levels. “I’m a practical person and learn through doing,” she says. “I completed some initial research into uni, as no one mentioned apprenticeships, but I knew I wanted to work.”

“I visited a friend who’s at uni, and met people there doing the same thing as me, but not enjoying it – and not getting paid to do it.”

What does she wish school had done to better support her? “It was only because my tutor talked about alternatives to university like apprenticeships that I started looking into them.

“I’d have liked college to have given me more input with CV writing and what’s expected at job interviews. I also wish they’d talked to us about how pay works, and the paying of tax and pension contributions.”

How to help work-focused students find their path

As adults, we know uni isn’t the ‘be-all and end-all’ of our students’ post-school plans, notes Hannah Day – but has anyone told them that?

Unlike the UCAS route, which gives you one form for over 65,000 courses, those looking at work and apprenticeships are faced with a different application process for each option they choose to pursue.

How should we as educators make sure we offer relevant support that can help our work-focused students navigate these varied paths?

Prepare the student

When talking to some ex-students who took the work route, several came back with a common observation – that they felt uni had been presented to them as the option, with little mention of alternatives to university.

I knew that we had, in fact, talked to them about the full range of options available, which made me wonder if words such as ‘apprenticeship’ are fully understood.

We may need to do better at laying out students’ possible post-school routes, but that will only be valuable if we clearly explain what each one actually means.

Next, we need to prepare students more fully with the practical elements of their applications. Uni students routinely have their personal statements read and re-read until they’re precisely presented celebratory accounts. Are other students’ CVs and covering letters given the same level of focus?

You may be able to stream students into different tutor groups depending on the routes they have selected, but this is tricky for the many who won’t have made up their minds – so ideally, you’ll need to prepare for both options.

Either way, lay out a given program as best as you can, ensuring that students complete not just the basics but also receive personalised careers advice, guidance on how to search for jobs online and mock interview practice.

Remember that they will additionally need help with how to present themselves and interact professionally.

Explain what initial information will be most important to know when they enter a new workplace, what to do if they’re unsure when in a working environment, and the roles played by mentors and unions. What may be obvious to us will be all new to them.

Prepare the parents (and ourselves)

One ex-student I spoke to wished that school had communicated with her parents and allayed her mother’s concerns: “My grandad has been to Oxford; mum thought I wasn’t going to go anywhere if I didn’t go to uni, but now she is so happy, and can see I made the right choice.”

As teachers, we tend to be the products of a university education and can often be ‘uni snobs’ (previously guilty).

However, I know now that university is only better if it’s the right choice for the student. I’ve worked hard to overcome my own biases, and will actively help parents, when needed, to do the same when it comes to alternatives to university.

One simple way is to celebrate our non-uni alumni as much as those with letters after their names. Do you know of any ex-students with notable accomplishments achieved via a vocational route?

Could they be persuaded to engage with the school, and inform and inspire your next set of leavers?

These steps will help us to better prepare our students. With a well-organised and relevant programme in place, we’ll be able to more fully demonstrate the value that all routes have, and encourage greater confidence in parents, whichever route their child chooses.

Prepare the workplace

This area is so much bigger than our own institutions – one that calls for a mix of both attitudes and policy.

As someone specialising in creative education, one reason I’ve found the ‘work route’ hard to grapple with is the frequent lack of obvious links and opportunities – which to me, makes no sense.

Website designers, effective social media managers, illustrators and graphic designers continue to be in high demand, making these roles ripe for work-based training.

For now, however, the only local option open to my students remains digital marketing. Despite government promises, the creative industries are still a hugely underdeveloped area within the field of apprenticeships.

If you’re the teacher of an academic course, be clear as to what jobs can emerge from your area of study and work back from there.

Are there any related apprenticeships students could pursue? Who are your local providers, and how can you work better with them?

One route we’ve found to be successful for us is to make links with small local businesses who want college leavers they can train.

While this doesn’t provide formal qualifications, it echoes the old apprenticeships model and can work very well.

We’ve built relationships with a number of local businesses via our annual careers day. Students get to take part in initial meetings with businesses that are relaxed, but have previously resulted in employers later asking students to formally apply for work.

Irrespective of whichever approaches may be right for your school and students, the key is to not see work as a second-class route, but rather as the high-value option it is.

Hannah Day is head of art, media and film at Ludlow College

Digital apprenticeships – How students and employers can benefit

Olivia Wolfheart explains how a digital apprenticeship can serve as a gateway to a rewarding, well-paid career…

Tech skills have never been in such high demand by employers. However, there remains a shortage of people with the required knowledge.

Once appropriately trained and qualified, some may therefore be able to pick and choose from a range of job prospects, put out there by firms lacking the necessary expertise.

Indeed, digital skills are becoming ever more vital across a range of sectors. This includes everything from construction, health, media, retail, travel and hospitality, right through to the more traditional banking and engineering.

Digital apprenticeships

Name an entry level role, and chances are that candidates will be required to possess some form of digital skills. The digital apprenticeships currently showing most demand include those in the areas of:

- business analytics

- software development

- digital marketing

- cybersecurity

A digital marketeer, for instance, will likely find themselves helping deliver promotional campaigns via social media.

A cybersecurity expert will be engaged in pursuing computer hackers. A data analyst will be tasked with providing the facts and context for crucial decisions. Or perhaps artificial intelligence or machine learning appeals?

Then there’s working as a business analyst. Here, the day job may involve looking at how companies can make the best use of their technical systems and using data analysis to create further efficiencies.

Working while learning

Digital apprenticeships last a minimum of one year. They’ll typically see the apprentice spending 80% of their time learning and getting valuable experience in the workplace. They’ll then spend 20% ‘off the job’, participating in structured training.

Apprentices thus benefit from simultaneously earning a wage and gaining qualifications, with no cost involved for the training itself.

The qualifications needed to commence digital apprenticeships will largely depend on its level, the organisation involved and specific job role.

Level 3 apprenticeships are approximately equivalent to two A Levels. Level 4 apprenticeships are equivalent to foundation degrees, while higher-level apprenticeships are equivalent to degree level and upwards.

Yet for all the opportunities and variety of experiences available, it’s still the case that young people tend to view careers based around digital skills, computing and technology in a very particular way.

Digital dimension

The careers to which young people are most readily attracted tend to be highly visible. Think doctors, vets, sportspeople, teachers.

However, it’s worth driving home that these areas of employment all contain a digital dimension to them. Digital health solutions, for example, or the technology solutions now routinely deployed in classrooms.

Young people are often driven to improve the world in which we live. This opens up numerous opportunities to demonstrate how technology can help.

Examples might include the range of ways in which technology is being used to combat climate change (such as improving waste management schemes in smart cities) and improve our overall levels of security (by protecting individuals and businesses from fraud and cyber attacks).

Relatable careers

A career in technology opens the door to a process of continual upskilling and pathways out to numerous exciting sectors.

Whichever path students eventually choose for themselves, if they possess up-to-date digital skills and the ability to apply them, their employability will increase considerably.

A career in computing will help to enhance a number of transferable skills, including computational thinking and logical problem-solving.

A great way of making such careers more visible and relatable can be to take learning outside the classroom on occasion. Or you can bring the outside world in.

There are numerous competitions and events open to schools. These are designed to inspire and inform young people about the career opportunities available to them in tech. Many teachers report finding such events helpful in positively influencing students to pursue technology-related career options.

At larger scale events, there will tend to be technology professionals present who are willing to visit local schools, provide talks and demonstrations and even potentially mentor certain groups or individual students.

By showcasing role models in technology, breaking down stereotypes and bringing to life the exciting, creative and collaborative opportunities technology allows for, we can make tech careers much more appealing to young people.

Olivia Wolfheart is a membership engagement manager at BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT and a former GCSE computer science teacher.