Shakespeare Week – Best primary resources and worksheets for 2024

Shakespeare Week 2024 takes place between 18th-24th March, so check out these great William Shakespeare activities, ideas and lessons for primary schools…

- by Teachwire

What is Shakespeare Week?

Shakespeare Week is the annual national celebration of Shakespeare in primary schools, organised by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Since its launch in 2014, over eight million primary school children have had fun, first experiences of the world’s greatest writer.

When is Shakespeare Week?

In 2024, Shakespeare Week takes place between 18th-24th March.

Shakespeare Week teaching resources

Shakespeare mental health and wellbeing lesson plan

Do you wear your heart on your sleeve? Are you sometimes the green-eyed monster? Although Shakespeare wrote over 400 years ago, the creative language he used to describe the human spirit remains relevant today.

These free emotional wellbeing activities will help your pupils to become Will’s Wellbeing Warriors as part of your Shakespeare Week celebrations.

Official Shakespeare Week resources

Michael Rosen shares his poem for Shakespeare Week 2023 from Shakespeare Birthplace Trust on Vimeo.

Log in or register for free on the official Shakespeare Week website and get planning for Shakespeare Week 2024.

There’s a wealth of resources, ideas and videos that guarantee rich and memorable learning experiences while still meeting key curriculum requirements. Unleash children’s creativity as they make books, sing, dance, perform and create.

Creative writing

There’s a bookmaking resource pack containing over 50 ideas for making a Shakespeare-inspired book, enabling children to explore a variety of writing styles and genres while having fun.

Children can also become Will’s Word Warriors with beautifully illustrated activity booklets – but beware of the Shakespearian insult generator contained within!

Online broadcasts

In 2023 there was a special assembly filmed in Stratford-upon-Avon with kids’ TV presenter Ben Cajee, which you can still watch online. There was also an inspiring workshop with children’s author and poet Michael Rosen and a drawing workshop with Horrible Histories artist Martin Brown.

Head to the official Shakespeare Week site to find a whole host of extra activities and ideas.

“A really inspiring week, where the children loved playing with words and ideas, learning language without realising!”

Teacher testimonial

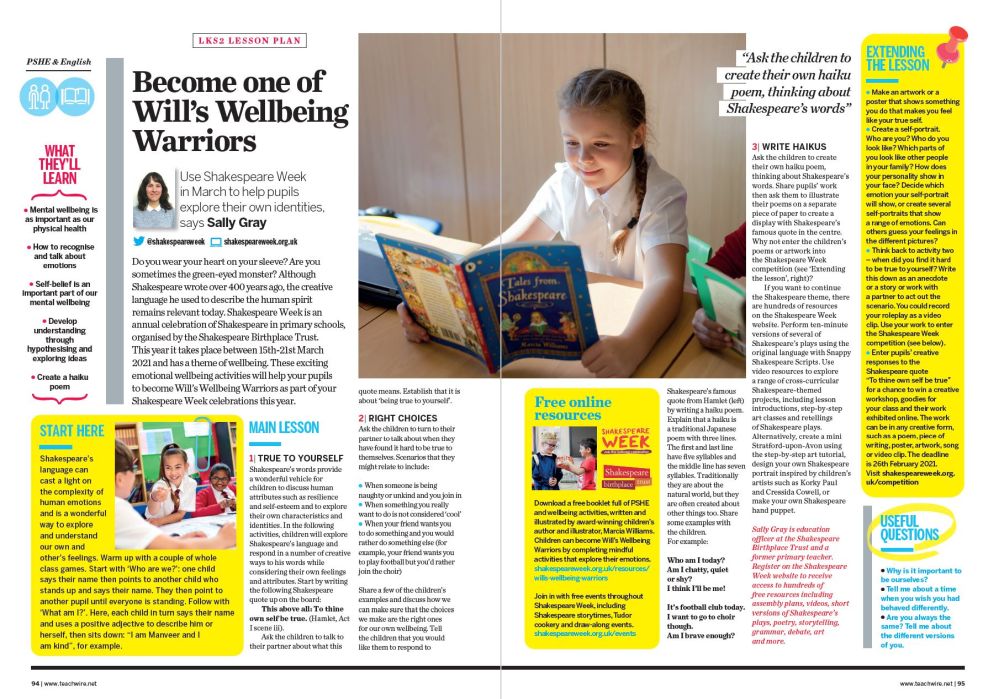

UKS2 comprehension pack

Use this UKS2 comprehension pack from Plazoom to learn about Shakespeare. Pupils will find out about Shakespeare’s life, legacy and how he became a writer.

Read the biographical text before answering questions. You can also use the biography as a model text/WAGOLL for your biography unit.

KS2 English lesson plan

By going behind the scenes and learning more about the historical context, Shakespeare becomes far more approachable.

In this free KS2 English lesson plan pupils will learn:

- To make inferences from the text

- To develop their summarising and prediction skills

- How to write effectively for a range of purposes and a specific audience

- How to use dialogue to convey information about characters

KS2 drama lesson plan

Studying Macbeth in KS2 can give pupils access to a fascinatingly complex world which is more than within their reach. This lesson plan from Marc Bowen shows you how to use the immersive power of drama to bring Macbeth to life in your KS2 classroom.

KS1/2 English lesson plan

Created for Shakespeare Week 2018, this free lesson plan lets children discuss and evaluate how Shakespeare used language.

It teaches children to form nouns by compounding and how to recognise compound words. Pupils will use drama approaches to support understanding of the meaning of phrases.

Shakespearean insults worksheets

William Shakespeare was a master wordsmith and his plays featured language that we still use today. His writing contained many insults and cutting remarks that would make people wince even now!

Use this Amazing Insults resource from Plazoom to explore the language he used to insult, and to create your own Shakespearean insults and infer their meaning.

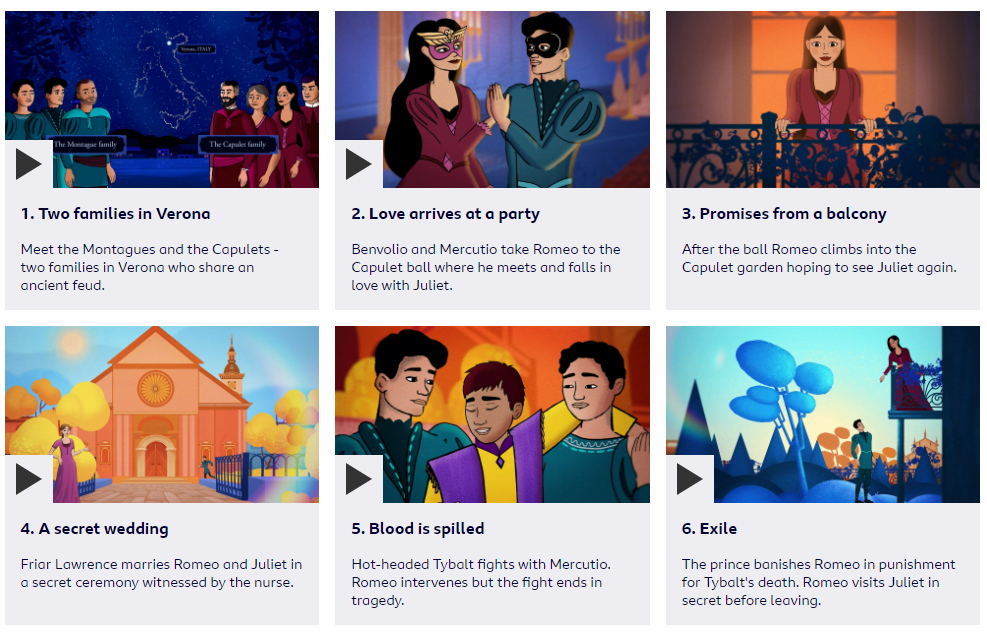

BBC Shakespeare teaching resources

Watch a nine-video animated version of Romeo and Juliet, alongside comprehensive teaching notes, worksheets and activities. Or take a look at similar resources for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Macbeth and The Tempest. Check out all the resources.

The Tempest unit of work

A wonderful story full of magic and excitement, The Tempest deals with themes of revenge and forgiveness, power and responsibility. It even has a comedy subplot. What more could you ask for as an introduction to Shakespeare?

This free unit download contains a three-week plan for teaching The Tempest in KS2, with explanatory notes.

Cross-curricular activities for KS1 and KS2

Give children a fabulous first experience of the world’s best known writer by exploring Shakespeare’s stories with these cross-curricular activities from Sally Gray, education officer at The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust…

Create a Shakespeare portrait

Make oak gall ink and create a pen and ink Shakespeare using the kind of ink he would have used to write with.

To make oak gall ink you need to collect a couple of good handfuls of oak galls and crush using a pestle and mortar.

Place in a pan and cover with water, pop in a piece of iron such as an old horseshoe. Bring to the boil and simmer for about 20 minutes until the tannins are released and it is a nice brown colour. Strain and allow to cool.

You can also cheat by buying replica oak gall ink online!

“Use an app such as ‘Face swap’ to add funny effects”

Alternatively, make an abstract Shakespeare. Draw a sketch of Shakespeare and then use a tablet to take photographs of the portrait.

Use an app such as ‘Face swap’ to add funny effects. Create a selection of images that show a range of thoughts and emotions.

Why not hold your own online or physical exhibition of Shakespeare portraits?

Sail to the isle of noises

Use air-drying clay to create the isle of noises from The Tempest.

Add characters from the play or specific landmarks such as a shelter for Caliban. Place the island in a water tray. Make rafts to sail to the isle of noises using recycled corks, elastic bands, cocktail sticks and card for the flags.

Why not then create your own soundscape of sounds and sweet airs to bring the isle of noises to life?

Invite the children to stand in a large circle and explain that they are going to create a soundscape. A soundscape is made by creating an immersive environment using body percussion and voices to set a scene.

Talk about the noises that might be heard on the magical isle, such as birds tweeting, waves lapping, sand crunching, trees blowing gently in the breeze, creatures calling and so on.

“‘Conduct’ the orchestra to create your soundscape”

Try out each suggested sound and then, while remaining in the circle, divide the children into small groups, giving each group a sound.

Explain that you will be a conductor and agree on signals for making the sounds quieter, louder, stopping the sounds, bringing sounds in and so on.

‘Conduct’ the orchestra to create your soundscape. Ask for volunteers to take turns to conduct.

Write a poem

After creating your soundscape, use the sounds and emotions explored as the starting point for a simple three-line poem.

For example, using The Tempest storm as an example, start with a sound (the sailors howling) then add some description, eg ‘The terrified sailors, horribly howling.’

Next, ask the children where the action is taking place (on the deck). Describe this location (salt-soaked). Line one now reads, ‘The terrified sailors, howling horribly on the salt-soaked deck’. Repeat this process to add two more lines.

Immerse yourself

Work with the children to design a ‘narrative environment’ or ‘storyworld’ in your classroom or school library that picks out a key or magical moment from one of Shakespeare’s stories and offers an immersive place for children to delve deeply into the story.

Using top tips from The Story Museum in Oxford here are some ways to create A Midsummer Night’s Dream storyworld:

- The scene: The story lends itself to a beautiful story space through its setting in the woods at night. Use woodland coloured drapes and bring in some branches to attach to the display boards. You could also bring in large pot plants as additional foliage. The children can add magical elements such as decorated pebbles and pine cones, fairy figures (home-made or bought).

- The objects: All of Shakespeare’s plays have evocative objects in them, and in A Midsummer Night’s Dream the characters have some intriguing accoutrements about their person too! Has one of Titania’s fairies, such as Mustardseed, dropped her scented wings? Has Puck hidden his Love-in-Idleness concoction somewhere?

- The senses: Add some twinkling fairy lights and make a recording of the children performing a ‘dream soundscape’ for a forest soundtrack.

Explore his language

About a thousand words that we use today are first recorded in Shakespeare’s poems and plays. Often he was simply the first to write them down, but he also invented words to express the meaning he had in his head.

Some of the words first found in Shakespeare include ‘fairyland’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), ‘amazing’ (Richard II) and ‘squander’ (The Merchant of Venice).

“Some of Shakespeare’s devices for making new words included adding a prefix such as ‘un-’”

Language is constantly changing and children can learn a lot from discovering how Shakespeare used words creatively.

Some of Shakespeare’s devices for making new words included adding a prefix such as ‘un-’, meaning ‘not’, as in ‘uncomfortable’. He also added suffixes such as ‘-less’, meaning ‘without’, as in ‘noiseless’.

Challenge pupils to use a prefix or suffix in new ways to create words. For example, which words could they create if someone took away their bike (‘unbiked’ or ‘bikeless’)?

Pounce a portrait

Nowadays if we want to make a copy of something we can simply photocopy or scan it. In Tudor times, the technique for reproducing a picture was called ‘pouncing’ and can easily be recreated by children to good effect.

Find a simple image of William Shakespeare and place a sheet of tracing paper underneath the image, secured with paper clips.

Rest the image and tracing paper on a piece of foam then prick through the lines of the image with a tapestry needle or awl. Place the pricked tracing paper onto a clean sheet of paper and rub charcoal through the holes.

Remove the tracing paper and blow away the excess charcoal to create a dot-to-dot image which you can join up to make an outline. Add colour with chalk pastels or paints.

Cook a Tudor dish

Sweet frumenty was a popular winter dish in Tudor times. It tastes like a fruity porridge. Follow this simple recipe from Mistress Sarah at Mary Arden’s Farm – home of Shakespeare’s mother, to make your own delicious dish:

Ingredients (makes four bowls):

- 150g pearl barley

- 500ml single cream

- Two tbsp clear honey

- ¼ tsp cinnamon

- ½ cup raisins

- ¼ tsp nutmeg

Boil the barley in a large saucepan of water until firm but cooked. Leave to drain. Add all the other ingredients to the saucepan and heat gently to a simmer.

Add the drained, cooked barley and heat together, stirring thoroughly. Serve hot.

Is Shakespeare too tricky for primary pupils?

My experience tells me otherwise, says primary school teacher and education consultant Stuart Rathe…

The other week, I told my Year 5 class the story of Cymbeline, by William Shakespeare. It’s a lesser-known late work that plays out as a sort of ‘Shakespeare’s Greatest Hits’.

There’s a wicked queen, a girl disguised as a boy, a faked death, mistaken identities, war, romance and an audacious and unexpected last-minute appearance from the god Jupiter. You name it, Cymbeline’s got it. My class were blown away.

From the gruesome (Macbeth) to the fantastical (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), Shakespeare can be a huge hit even with very young children. And with the right resources, a Shakespeare story can make a fantastic English unit of work, lending itself to drama, reading and writing outcomes.

Telling tales

There’s a difference between reading a story and being a storyteller. I remember, as an early career teacher, telling the story of Hamlet to a lower Key Stage 2 class. Conjuring up castle battlements and an armour-clad ghost as if from nowhere immersed my class in the story – despite the dreaded post-lunch-slump timeslot.

If you’re not familiar with the story you’re going to introduce, use a simple plot summary to write key points on cue cards before you start. When I prepare for a storytelling session, I usually grab some rudimentary props as well (a paper hat for a crown, a beaker for a poisoned chalice). I then give these to some of the children and encourage them to help me act out the story.

Often, I find pupils are still acting out the story at break and lunch times, putting their own spin on a classic tale. Investing time in immersion at the start means pupils are engaged in their learning outcomes for the remainder of the unit.

Freeze-framing

Ian McKellen once said, “I’ve never heard anybody say, ‘Oh, we had the most wonderful class where we read Act I, Scene 3.’” He was right.

After an initial storytelling immersion, a good way to create ‘instant’ Shakespeare productions is to use short summaries of the plot in ten numbered points, to produce freeze-framed dramatisations.

BBC Teach has animated versions of Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest, including accompanying teacher resource packs, which include ten-point plot summaries.

With pupils in groups of five or six, divide plot point summaries amongst groups, and give them a short time to devise a frozen tableaux representing each plot point.

Watch the freeze frames back in chronological order, prefaced by one member of each group reading out their plot point summary. In 30 minutes, your pupils will have successfully retold a Shakespeare story.

Afterwards, I like to blow up the ten points onto ten A4 sheets – one point per sheet – and display them chronologically on the classroom working wall, to give pupils a sense of the shape and structure of the story.

This also works as a great visual prompt in class, allowing you to ask questions like, “How do you think Lady Macbeth feels at this point in the story, and why?”

Tackling language and rhythm

A mention of Shakespeare’s blank verse, also known as iambic pentameter, might trigger vivid and panicked flashbacks to your own school experiences. But it really needn’t be scary or dull. In fact, it can be a lot of fun.

A blank verse follows a 10-beat pattern – five pairs of beats, with a weak stress on the first beat and a stronger stress on the second beat. (Say it out loud: De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM).

If you clap out the rhythm with a group of Key Stage 2 pupils, I guarantee they will tell you it sounds like (a) a heart beating and (b) a horse galloping. Every time.

Iambic pentameter is found in some of Shakespeare’s most famous lines such as: “Once more unto the breach dear friends once more” or “I never saw true beauty till this night”. But it follows a natural rhythm that we still find in modern English, as with: This play is perfect for my Year 5 class.

I introduce iambic pentameter with clapping games. Have pupils sit in a circle and clap some simple rhythms for them to echo back, then introduce some examples from Shakespeare.

Key Stage 2 children love to identify and play with this rhythm once they’ve got to grips with it. I ask pupils to write their own iambic pentameter poetry, based on stills of key moments from Shakespeare animations. These make a wonderful incidental written outcome in the middle of a Shakespeare unit.

Watching different interpretations

Shakespeare’s work is timeless, with modern retellings sitting side by side with the classics. I like to show pupils stills and clips from different versions. Try watching the catchy pop video animation of Romeo and Juliet from Shakespeare in Shorts:

Alongside this, try the BBC Teach animations. Is the storytelling clear? What impact does a modern setting have? What age range is this version suitable for?

Engagement with different versions of a Shakespeare text is good training for Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4 study, where pupils will be expected to explore stagecraft and performance choices.

Exploring key scenes

I use slightly abridged versions of key scenes (with original Shakespeare language) to get pupils to study scenes in detail and develop their performance skills. I usually choose examples with only two characters.

I put pupils in groups of four, and use a technique called ‘ghosting’. This involves two pupils taking on the roles. Another two pupils stand at the performers’ shoulders, holding the script and quietly feeding lines to them.

These ‘ghosts’ allow the performers to be hands-free, making their performances more expressive. You will find that they soon become familiar with the text and require less feeding from the ‘ghosts’.

Another fun script activity is to pretend the scene is being played out on Eastenders. Take the essence of the scene, improvise, and play around with it in modern language.

I like to take pupils back to the original script after this improvisation exercise, but ask them to remember the ‘modern’ emotions and feelings they had when delivering the Shakespearean lines.

By acting out key scenes, pupils empathise with characters and can then produce more expressive and impressive writing in character.

How to feel confident teaching Shakespeare

- Use a simple plot summary to write key points on cue cards and become a storyteller.

- Create ‘instant’ Shakespeare productions by using short summaries of the plot in ten numbered points.

- Introduce pupils to iambic pentameter with simple clapping games.

- Make use of play extracts for acting and showing back. You’ll be surprised how prepared pupils are to take risks with Shakespeare’s language if they have a prior understanding of the story. BBC Teach animation resources include adapted script extracts.

- Don’t be afraid to draw on modern references. Modern dramas or soap opera clips could be great ways to help children access a melodramatic Shakespearean acting style.

Stuart Rathe is a primary school teacher and education consultant. A new BBC Teach animation of Romeo and Juliet can be found at tinyurl.com/bddhdx43.

Pie Corbett Shakespeare unit

By taking small pieces from his plays and experimenting with the language, your children will soon be producing sonnet-worthy work. See how educational trainer and writer Pie Corbett taught Shakespeare to Y5…

Session 1 – Shall I compare thee to a bacon butty?

Of course, everyone had heard of Shakespeare and most knew that he was a playwright. We spent a little time in which I filled in the background, before introducing the idea for the day – we would try to write like Shakespeare.

To start off, I read them sonnet 18, which starts with the words almost every teacher will know, ‘Shall I compare thee to a Summer’s day?’

First, we cleared the basic idea of the poem out of the way. He’s praising his girlfriend and saying that even when she grows old, she will still be beautiful because he has captured her forever in the poem.

Making comparisons

We focused on the opening comparison. Of course, imagery like this is, in a way, a total lie. When Robbie Burns wrote, ‘O my luve’s like a red, red rose’ he was trying to flatter her – to make her sound amazing and appealing.

The truth is that she would have been nothing like a real rose.

I suggested that we try out some similar comparisons by thinking about someone we admired and then asking them with what they would like to be compared.

To help, we listed all sorts of unusual and amazing things for the comparisons:

- flamingo

- snow storm

- crescent moon

- frost on the path

- bacon butty

- steam on the window

- tiger’s eye

- snake’s skin

- sheep’s wool

- conker

- polished car bonnet

- red bus

Surprising ideas

We selected a few of the ideas and, with a little polishing, wrote together – with me scribing on the flipchart. We discussed how some ideas made the person sound good and others sounded ominous, funny or surprising.

Shall I compare thee to…

- frost glittering on the hedgerows?

- a tiger’s amber eye, coldly staring?

- a bacon buttie and a cup of sweet tea?

- the six sides of a mathematician’s dice?

We talked too about how some of the ideas sounded familiar and therefore did not have so much effect. The ones that worked best were surprising and totally fresh.

These brought a new idea into the world. We kept the old-fashioned word ‘thee’ as we felt that it ‘sounded better’ than the word ‘you’, which seemed to have less emphasis when read aloud.

Memorable lines

We then tried imitating other memorable lines that I had carefully selected as possible creative catalysts.

For instance, in Anthony and Cleopatra a soothsayer boasts, ‘In nature’s infinite book of secrecy / A little I can read’.

So we invented different books – a book of sorrow, a book of hope, a book of dreams, etc, and then created similar lines using the same Shakespearean pattern. For example:

In the goblin’s horrifying book of terrible torment, a little I can read…

– Izzy, age 9

Once the children had the basic idea, I had up my sleeve a number of other lines that could be used in the same way.

We talked them through and together invented possibilities. Some children selected only one idea and wrote many lines, whilst others experimented with different lines, writing several ideas of their own for each.

Freedom to choose

I suspect they enjoyed the freedom to choose what to concentrate upon, but were also supported by a strong scaffold that meant everyone could succeed.

Here are a few examples, showing Shakespeare’s original and a child’s response. We ended the session by reading aloud lines and commenting on what we liked.

Original: But soft! Methinks I scent the morning air

Child’s: But soft! Methinks I see the sunlight drifting

Original: Peace! How the moon sleeps

Child’s: Peace! How the hills still

Original: The stars will kiss the valleys first

Child’s: The stars will run around the world

Session 2 – Getting dramatic

Having warmed up our Shakespearean tongues, in the next session we moved on to looking at act 2, scene 1 of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

This is where Puck meets a fairy: ‘How now spirit? Whither wander you?’

In pairs, the children tried out this greeting and invented replies. We heard a few and then I read them what the fairy in the play replies:

Over hill, over dale,

Thorough bush, thorough brier,

Over park, over pale,

Thorough flood, thorough fire.

I do wander everywhere

Swifter than the moon’s sphere.

And I serve the fairy queen

To dew her orbs upon the green.

The cowslips tall her pensioners be.

In their gold coats spots you see.

Those be rubies, fairy favors.

In those freckles live their savors.

I must go seek some dewdrops here

And hang a pearl in every cowslip’s ear.

Farewell, thou lob of spirits. I’ll be gone.

Our queen and all our elves come here anon.

Rough idea

Again, we sorted out the rough idea. The fairy goes everywhere, even through flood and fire, faster than the moon spins, working for Titania, the fairy Queen, making fairy rings.

The cowslips are her royal bodyguard and their speckled petals are sweetly-scented.

The fairy has to hang pearl earrings on the cowslips and so bids Puck farewell before the Queen and her elves arrive.

The fairy works for the fairy Queen and has to toil through the night dropping dew on the cowslips to make the world a prettier place.

We took the lines and read them together, working on saying them dramatically.

We tried varying how to say them – some loud, some soft, some fast and some slow with dramatic pauses.

The children then worked in groups of about four or five, reading the verse and developing some simple movements to accompany their interpretation.

This took some time before we watched each group.

Session 3 – A fairy’s work is never done

In the next session, we wondered what other tasks a fairy might be asked to fulfill.

I read them some of my ideas based on the lines ‘I must go seek some dewdrops here / And hang a pearl in every cowslip’s ear.’

Here is the model poem that I read to them:

I must sprinkle flecks of frost

On the crisp autumn leaves.

I must seize the hiss of an adder

And hang dew on a spider’s web.

I must help the blind mole

Build pyramids of earth.

I must sharpen blades of grass

And put freckles on a child’s face.

I must ride on a bumblebee’s back

And polish the salmon’s scales.

Farewell, thou aged beggar. I’ll be gone.

After reading it to them, I took initial responses. We then read it line by line, discussing what the words meant.

I pointed out that I had not rhymed and asked them not to rhyme either. Explain that you’re more interested in their own ideas about what a mischievous fairy might do.

Then we worked together to list ideas for the sorts of tasks that a fairy might be given so that everyone had ideas to draw upon. Though when the children wrote, most of them used their own inventions.

Session 4 – Boil and bubble; it’s no trouble!

For the final session, I read the children the wonderful version of Macbeth in Shakespeare Stories by Leon Garfield.

Alongside this, I read them the whole scene from Macbeth where the three weird women chant:

Eye of newt, and toe of frog,

Wool of bat, and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork, and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg, and howlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

Creating your own version

Once again, we performed the piece with the children working in threes, circling imagined cauldrons and chanting.

We then used the basic pattern to create our own versions.

This is actually harder than you might imagine – it is worth trying it out yourself before you teach the session.

First of all, make a long list of possible ingredients with the children. Anything can be used – parts of animals, things found in nature or the city, things from home or school, toys, parts of vehicles.

The hard part is assembling the ideas so that you write rhyming couplets.

Luckily, the first part of each line does not have to rhyme so start boldly. For instance, you might agree upon ‘Bark of a tree’.

Now you will need to add on a second idea. This one will be crucial because you will have to find a suitable rhyme.

Let’s imagine someone suggests ‘Bark of a tree and wheel from a car’. Now you have to invent a second line that ends with a rhyme for ‘car’ – bar, afar, star, scar and tar are possibilities. Of these four, ‘star’ or ‘scar’ are probably the easiest and might give you:

Bark of a tree and wheel from a car

Heel of shoe and gleam from a star

Or

Bark of a tree and wheel from a car

Heel of shoe and scab from a scar

Tussling with rhymes

If you cannot find a rhyme for the end of a line then you will need to change the final idea. It can make the task far easier if you have copies of the Rhyming and Spelling Dictionary.

Most rhyming structures are too hard for children, but this structure means they can be creative, tussle with the rhymes and satisfy their desire to produce a poem that sounds powerfully rhythmic when read aloud.

Here are the opening lines of a poem produced by two Year 5 children working together. You will notice that I suggested they began by using a few of Shakespeare’s lines to help them ‘hear’ the rhythm:

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog.

Wing of an eagle and claw of a cat,

Paw of a panther and tail of a rat.

Brick from a wall and shoe from a pony,

Crab from a pool and smile off a phoney.

So we came to Shakespeare as writers rather than readers. Through trying out the same patterns and ideas, they came to read and enjoy his lines with a different eye and ear.

They were fellow writers who had also tussled to create metaphors or adopt adventurous patterns.

All this breaks down the mystery of the distant language and opens up the possibilities of internalising the patterns and stances of the world’s greatest writer.

Where there’s a Will, there’s a way

What helps children get to grips with Shakespeare?

At the end of my final lesson with that Year 5 class, I asked them to write me an evaluation, especially what had helped them as writers.

Here are a few of their comments that I found helped me understand what in my teaching had been useful to them as learners:

- It was easier for me to write because of the pictures and models.

- I have learnt it is easier to write a poem when I have another poem to look at.

- When Mr Corbett showed us on the flipchart it was easier to understand.

- Yes, I’ve learned a lot, but the thing is he broke it up into little stages.

- I find it easier to write because of thinking time. He explained words.

- You’ve helped me a lot with writing on the board.

- Pie tested your words and made you think of the best word you can use. It also helped me that Pie put all of the words in different sections.

More great ideas for teaching Shakespeare

Make plays like Hamlet, Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet relevant to your class no matter what the age range with these activity ideas from Stuart Rathe, education manager for Shakespeare Schools Foundation…

Tell a Shakespeare story

There’s a real difference between being a storyteller and simply reading a story. As a Year 4 primary teacher, I remember telling the story of Hamlet to my class. It’s my favourite play, and I know it well.

Conjuring up spooky castle battlements and adding actions (a stab through the curtain to kill Polonius!) really immersed my class in the story; you could hear a pin drop.

Even if you don’t know a Shakespeare story well, you could use a simple plot summary to write key plot points on cue cards.

Rehearse your storytelling at home and you’ll have pupils eating out of your hands. Already, you’re dealing with a living story rather than text on a page.

Engage reluctant readers

Shakespeare’s language can be daunting but there’s something out there for everyone. There are some great manga and comic strip adaptations of Shakespeare on the market.

Shakespeare’s tragedies are full of gore and bloodshed: Macbeth is an excellent starting point and a popular primary school text. For Harry Potter fans, there’s magic aplenty in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The Animated Tales

There’s no better introduction to Shakespeare’s stories than these 30-minute animated abridgements, first shown on television in the early 1990s.

Iambic pentameter

Shakespeare’s blank verse, also known as iambic pentameter, sounds like it should be impenetrably tricky at Key Stage 2. In fact, it’s huge fun. It acts as the heartbeat underscoring Shakespeare’s verse.

It follows a ten-beat pattern with the stress on alternate beats (De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM, De-DUM).

You can find it in some of Shakespeare’s most famous lines, such as:

Once more unto the breach dear friends once more!

But it can easily be mimicked in modern English, as with:

I’d like to have another cup of tea!

Key Stage 2 pupils really enjoy making their thoughts fit this rhythmic pattern. Before they know it, they’re writing iambic poetry inspired by Macbeth’s witches or Puck and his mischievous tricks.

Freeze framing

Why not get acting straight away? Shakespeare should come off the page as soon as possible, and using ten-point play summaries provides the perfect format for quick storytelling opportunities.

With pupils in groups of five or six, divide plot point summaries amongst the class and give pupils a short period of time to devise frozen tableaux representing each plot point.

Watch the freeze frames back in chronological order, prefaced by one member of each pupil group reading out the plot point summary.

In 30 minutes, your pupils have successfully told a Shakespeare story.

Silent movies and movie trailers

It’s fun to compare old and new movie-making approaches, and it reminds pupils that Shakespeare is as relevant now as he ever was.

Watch Percy Stow’s early silent short movie of The Tempest. If your pupils are already familiar with the story they should be able to identify the key silent movie scenes and characters. They could even add their own dialogue and sound effects.

Finally, they could compare early movie-making approaches with modern productions, by viewing the trailer for Julie Taymor’s 2010 film version of The Tempest:

Consider a workshop

SSF provides Key Stage 2 workshops to give pupils an exciting introduction to Shakespeare’s work.

Take part in SSF’s annual festival

Watch your pupils fly as they command Shakespearean language on stage in front of an audience of peers, parents and the local community.

How to have fun with Shakespeare in primary

Make sure your pupils’ initial introduction to Shakespeare leaves them wanting to get to know him better with these ideas from Helen Mears…

How did you first encounter Shakespeare? Think back to that moment now.

Was it sitting in a classroom reading barely comprehensible text aloud? Was it on the stage or screen listening to someone with a cut class accent reciting the words with an unwavering reverence?

Or did you discover him by some other means? A passionate teacher? A parent or relative who couldn’t wait to share him with you?

First encounters

First encounters with William Shakespeare are crucial. They shape future attitudes and perceptions of him.

A negative encounter can put someone off for life, a positive one can be the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship.

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s Stand Up For Shakespeare manifesto is already established in the education system with its three key tenets:

“Do it on your feet; see it live; start it earlier”.

‘Starting it earlier’ can easily mean introducing Shakespeare at Key Stage 1 and then developing and building on that work through Key Stage 2.

“First encounters with William Shakespeare are crucial”

Children of this age have a natural predilection for rhythm, rhyme and storytelling. These elements are inherent to Shakespeare’s work and are an excellent hook into the plays.

Get physical

One thing that is universal in the growing trend towards teaching Shakespeare in more engaging ways is to ensure that he isn’t made to seem excessively special or important.

The pleasure of the plays, particularly in performance, is their joyous irreverence, their imaginative play with language and their rich characterisations.

These are elements you can utilise when teaching Shakespeare to very young children.

It is also productive to approach the texts with a drama focus rather than an English one, making the topic more fun and accessible.

The DfE’s Shakespeare For All Ages and Stages publication suggests that storytelling, improvisation and role play be the focus of KS1 work. KS2 work can develop aspects of performance and dramatic approaches with cultural visits encouraged.

‘Whoosh’ activity

With your youngest primary children, I recommend an active and physical approach to the plays.

Achieve this effectively with a ‘Whoosh’. To do this activity, ask everyone to stand in a circle. Next, read a synopsis of the play.

“Once the pupils have a sense of the story you can begin to work with small scenes”

Encourage children to enter the story and act out the actions that are being described. Examples of Whooshes are available in the RSC Teachers Toolkit for Primary Teachers.

Once the pupils have a sense of the story you can begin to work with small scenes or extracts from the play.

Pick your play

There are particular plays which lend themselves well to working with young children for differing reasons.

You can approach The Tempest in at least two different ways. The first is to explore the storm scene at the beginning of the play.

The following activity is described by the RSC’s Joe Winston in the Journal of Aesthetic Education (2012).

Encourage children to recreate the storm using a range of percussive sounds and through vocalisations based on snippets of wording from the play itself.

You can easily chant the Boatswain’s short and exclamatory lines. Use a cloth or parachute to simulate the tempestuous waves.

“Encourage children to recreate the storm using a range of percussive sounds”

Some children can take the roles of Ariel and his weather spirits raising the storm.

This is an activity that would work well outside, particularly on a windy day.

Winston also explored the relationship between Prospero and Caliban via the angry language exchanged between the two.

Split the children into two groups and trade snippets of the insults from the text itself or those you’ve created.

Winston believes that trading such insults in a controlled environment allows children to safely experiment and play with slightly darker elements of language, something they naturally enjoy doing.

Feel the rhythm

Another way into Shakespeare’s work is to focus on rhyme and rhythm.

While most of Shakespeare’s works are written in blank verse, he does use prose and other rhythms for particular effects and purposes.

One of these is particularly appealing to children. The witches in Macbeth speak in trochaic tetrameter (four pairs of a stressed followed by an unstressed beat).

This is a rhythm familiar through nursery rhymes such as Mary, Mary Quite Contrary and the opening lines of Humpty Dumpty.

Shakespeare uses the rhythm to distinguish these supernatural beings from the play’s human characters and the chant-like sound of the language will feel natural to children.

Double, double, toil and trouble

As an introductory activity to Macbeth, use Banquo’s description of the witches in Act I, Scene III. Encourage children to use their bodies to visualise the witches. Ask them to move around the space, perhaps with added vocalisations.

The ‘double, double, toil and trouble’ segment of the play is perfect to use with children owing to the chant-like use of trochaic tetrameter.

Read the spell itself, with the children joining in for the refrain. Try setting the words to a simple tune. Again, this activity would work well outside. Your field or playground could become the witches’ blasted heath.

“Encourage children to use their bodies to visualise the witches”

Children can collect items to use in their own version of the potion which can then also be chanted together. You can also write these items into your own version of the spell.

Introduce props, masks or other elements of costume to add visual richness.

Use this activity to discuss the nature of witches. Consider the impact on Macbeth of listening to their spells and prophecies.

These ideas are just a start. You can easily adapt other plays to use with primary aged children.

The important things to remember are the focus on drama and performative elements. Give children the chance to work with even very short extracts or text scraps of Shakespeare’s original language.

Look for the characters or aspects of language that will appeal to your pupils. Then you will be well on your way to making their first encounter with Shakespeare a positive one.

- Shakespeare Week website

- Springboard Shakespeare guides by Ben Crystal

- Transforming the Teaching of Shakespeare with the Royal Shakespeare Company by Joe Winston

- Creative Shakespeare: The Globe Education Guide to Practical Shakespeare by Fiona Banks

- Teaching Shakespeare by Rex Gibson

- The Globe’s Playground website

- The RSC’s teacher resources

- RSC Shakespeare Toolkit for Primary Teachers

- British Shakespeare Association’s Teaching Shakespeare magazine

- Shakespeare For All Ages and Stages